Living in the Pacific Northwest means confronting the annual threat of wildfire, which makes understanding fire dynamics critical. At the University of Oregon, researchers from various fields are studying the effects of wildfire and how to create fire-resilient communities.

Wildfire season is getting longer, and fires are intensifying due to many factors. Chief among them is that climate change is creating drier, hotter weather that provides the perfect conditions for wildfires. Additionally, how we manage landscapes has great influence on the ignition and spread of fires.

Fire is a dynamic process and requires a multidisciplinary approach to thoroughly appreciate its complexities. Researchers in ecology, sociology, geography, policy and management, and anthropology are combining their unique perspectives to gain a comprehensive understanding of fire and its impacts on West Coast communities.

Looking at past fires to inform the future

One way of understanding how fire is changing to predict future changes is by looking at fire dynamics over millennia. Dan Gavin, a professor in the Department of Geography and a member of the Institute for Ecology and Evolution, studies long-term changes in the fire regime over thousands of years.

By adopting a long-term perspective, Gavin creates a comprehensive picture of how forest compositions have changed, consequently influencing the fire regime—patterns of how fires occur in an ecosystem. Understanding the causes of past periods of frequent fire informs projections of future fire regimes and enhances our understanding of the susceptibility of re-burning.

“In the Western Cascades, regrowth is rapid following fire, from sprouting shrubs, so burned areas, are filling in with blackberry and fireweed that are highly flammable,” said Gavin. “Each time a re-burn happens it increases the burned area a bit more. The paleo record shows evidence of the re-burns and the hazards they pose.”

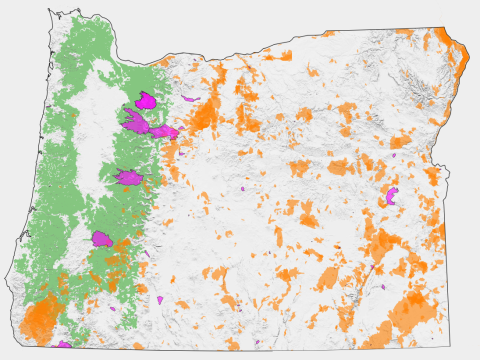

Another way to predict the effects of future fires is to examine the behavior of recent fires. Melissa Lucash, a research assistant professor in Geography and Environmental Studies, uses ecosystem models to project the species composition and carbon sequestration of future forests. Central to her research is the exploration of wildfire impacts and its implications for shaping forests.

Lucash is one of the lead developers of LANDIS-II a spatial model that simulates individual tree species. "This combination of capturing species-level and spatially interactive processes makes it different than most models,” Lucash explained.

An upcoming project that Lucash is leading will bring together field ecologists, fire modelers, and social scientists specializing in wildfire research. Their aim is to better simulate the impact of extreme fire events, like the Labor Day fires of 2020, on the landscape.

“The idea is to bring together different kinds of expertise to learn more about extreme wildfire events and then apply that knowledge to LANDIS-II to see if we’re representing those mechanisms correctly,” said Lucash. “Then, we'll improve the model to better represent that behavior.”

Using data from past fires, whether it’s data over millennia or over decades, provides valuable insights into the future of fire on our landscape. Understanding the intricate changes within the fire regime can better equip us to navigate future fire seasons under a changing climate.

Rebuilding forests after fires

Large, intense wildfires have the potential to transform landscapes and remove crucial native plants and animals. Following destructive disturbances, the natural recovery process can take years to fully restore the landscape. However, restoration ecologists are actively researching ways to enhance an environment’s capacity for self-restoration, thereby bolstering resilience.

The Hallett Lab explores ecology principles that can enhance restoration efforts with a focus on fostering plant coexistence and mitigating plant invasion. A graduate student in that lab, Ethan Torres, is looking specifically at the influence of fungi on native and invasive plants in a post-fire landscape.

Invasive species have incredible adaptability, allowing them to grow rapidly in poor conditions, which makes them the perfect opportunists to colonize post-fire landscapes. Torres is interested in the role mycorrhizal fungi play in the re-establishment of native plants and the introduction of invasive plants.

“Mycorrhizae are important for plant growth and community succession, so if you lose that fungal community, it can open up the area for invasive species,” explained Torres. “In some environments restoring those native mycorrhizal communities post-disturbance can prevent invasive species from colonizing. But in others invasive plants take advantage of the existing fungal networks and then colonize more successfully.”

Torres recognizes the evolving fire patterns and our relationship with fire, acknowledging their impact on his work. “We’re at this interesting part of our development as a society in terms of our relationship with fire. It’s important for us to view fire not just as a unidimensional occurrence; fire is dynamic and nuanced,” said Torres. “It’s exciting to be part of the efforts to better understanding that nuance and move towards viewing fire as less of an environmental hazard and more of a beneficial disturbance.”

The Ponisio Lab is dedicated to unraveling the intricate dynamics of plant-pollinator interactions across diverse environments. Graduate student Rose McDonald is interested in restoring pollinator habitats within timber forests—areas subject to intensive management for timber production.

McDonald is working with timberland owners whose land has been affected by wildfires to study the effects of salvage logging and the wildfire itself on pollinator populations. “Salvage logging involves clearing entire areas of dead, fallen trees and creating open spaces,” explained McDonald. “This presents an opportunity for us to plant enhancements or floral strips to help support some native pollinators.”

This work not only boosts native pollinator populations for the upcoming season but also contributes to future resilient populations. “The beautiful thing about these enhancements is that they introduce a community of native flowering species that will take root where they’re planted, but also disperse throughout the area,” McDonald expressed. “This helps establish more resources for bee communities and, in the future, when fire comes through, there may still be a robust native seed bank and thriving bee populations that will be able to withstand the disruptive impact of such events.”

Preparing people for fire

Fire is an integral part of the Pacific Northwest’s ecosystem, thus understanding the intricate relationship between humans and fire is essential for a successful future.

Mike Coughlan, an assistant research professor in the Institute for Resilient Organization, Communities, and Environments, and the associate director of the Ecosystem Workforce Program, looks at past fires to better elucidate human-fire interactions, with a focus on building resilience back into forests.

One way to enhance resilience in our landscapes is through prescribed fires, which involve the deliberate and controlled application of fire. “Prescribed fires burn at a lower intensity at a time when larger fuels are less dry, mitigating the risk of spreading,” said Coughlan. “By strategically implementing prescribed fire at the right time over time, we can reduce the accumulation of fuels that cause wildfire to spread.”

Coughlan defines his research as social ecological resilience. “It’s not just fortifying forests against fire,” explained Coughlan. “It’s about fostering a relationship with fire that integrates it as a natural component of our system. That’s the overarching concept that we examine from all kinds of perspectives.”

Current research extends beyond fostering resilience in communities and forests by emphasizing communication about wildfire smoke hazards and implementing more effective strategies for driving change.

Jess Downey, the manager of the Center for Wildfire Smoke Research and Practice, plays a pivotal role in understanding how communities prepare for and respond to fire, as well as assessing the effectiveness of smoke communication across different levels of governance.

“Right now, we’re focusing on interviewing air quality communicators,” explained Downey. “We’re trying to understand how air quality communication is talked about and examine existing research. Then, we’re going to use that information to inform our interviews with different air quality communicators.”

Effectively communicating the health risks posed by wildfire smoke is vital for community preparedness and adaptation to living with fire. However, communicating this complex topic to a broad audience from diverse backgrounds can be difficult. Downey’s experience in the health care field gives them a unique perspective on how different people understand and respond to communication concerning their health and safety.

“With my past experiences in health care as a Registered Nurse, I have some insight into how people perceive and process information and have experience in adjusting communication based on the knowledge level of the intended audience, whether that be through education or experience” Downey reflected. “Often times people are aware of the actions they should take but lack the money or resources to do so. Having these perspectives can be helpful because it provides a more grounded approach to communication.”

Research into the dynamic interaction between fire and humans creates communities that are better equipped to coexist with fire on the landscape. This research is crucial, particularly as the fire regime continues to change around us.

Viewing fire differently

For years, our society has been rooted in an anti-fire culture. However, some researchers are hoping to shift this perspective and foster a deeper understanding of what it means to coexist with fire in the West.

Amanda Stasiewicz, assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Studies, works at the interface between communities and government organizations. A significant focus of Stasiewicz’s research involves working to create more fire-adapted communities, which involves shifting our relationship with fire and reevaluating our response to ignitions.

“As humans on a fire-prone landscape, our approach shouldn’t just be fighting it; rather we should learn to live with that natural rhythm of the landscape,” Stasiewicz asserted. “That’s not going to look the same in every context. This approach will differ based on individual skills, values regarding the landscape, and the specific ecosystem."

As fire becomes increasingly common in the West, policy lags behind, resulting in a disconnect between the realities observed on the ground and the established procedures for responding to fire.

“One of the biggest things to recognize is that under our changing climate we’re currently seeing the need for revision outpacing what our policy system can create,” explained Stasiewicz.” “Hazard mitigation policy requires drastic and large-scale change, yet democracy and policy are typically defined by incremental change.”

Another group of UO researchers is actively engaging younger generations in fire policy discussions, with the aim of generating the changes required to foster fire-adapted communities through social transformation, community organizing, and policy reform.

Fire Generation Collaborative, also known as FireGen, was established in 2022 with a clear objective: to include and engage the diverse perspectives of young people in envisioning a fire-resilient future. Co-founder Ryan Reed, a UO alum and fire practitioner from the Karuk, Hupa, and Yurok tribes in Northern California, hopes to inspire a shift from the Western lens through which fire is currently viewed.

“Much of the current wildfire research is grounded in a Western-centric perspective,” noted Reed. “However, when addressing wildfires, it’s crucial to center on the impacted communities and the people engaged in fire management efforts.” To Reed and his colleagues, this means an emphasis on Indigenous knowledge, practice, and research frameworks.

Kyle Trefny, an undergraduate student and FireGen co-founder, draws on his experience as a wildland firefighter to gain insight on the challenges within the workforce and identify opportunities for creating a more equitable environment.

“As a firefighter, I’ve witnessed first-hand the harassment and marginalization that queer people face in a traditional firefighting paradigm,” shared Trefny. “In our efforts to both envision and conduct research that moves away from the current model, we draw on the concepts of Unangax Indigenous scholar Eve Tuck about desire-based frameworks.”

Meredith Jacobson, a PhD candidate in environmental studies and sociology, joined FireGen’s research team in 2023, bringing her expertise in community-based research to the table. Her aim is to continue advancing initiatives that center the voices and needs of individuals impacted by wildfires, with the ultimate goal of shaping a more equitable and resilient future. Reed, Trefny, and Jacobson are co-facilitating a research effort that combines quantitative surveys and qualitative listening circles to hear from young people across Oregon and northern California about their ideas, needs, and dreams for fire stewardship.

“We’re drawing from principles of participatory and collaborative research, actively involving community partners in shaping our project,” said Jacobson. “We’re also learning from Indigenous and anti-colonial methodologies, which emphasize centering relationships and fostering conversations where people can share from their own perspectives and knowledges.”

Shifting away from the perception of fire as a villainous force and instead recognizing its natural occurrence and potential benefits is imperative for adapting to the evolving fire regime in the Pacific Northwest.

As wildfires continue to impact our landscapes, the urgency for proactive solutions has never been clearer. Through ongoing efforts to strengthen community resilience and reshape our understanding of fire, current research charts a course toward a future where wildfires are met with understanding of the role they play in ecosystems and managed with compassion.