As a recently colonized landscape, Coos Bay is a case study for examining issues of indigenous and water justice. During the past 150 years, the estuary has gone through significant human-caused changes, including dredging, deepening, back-filling, and other modifications.

Ava Minu-Sepehr, an undergraduate fellow in the Office of the Vice President for Research and Innovation, uses mapping to examine the Coos Bay estuary as a space of both extermination and resistance by the Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw. While many decades of changes have massive repercussions for the health of the estuary, they also represent a deliberate effort to eradicate and decimate peoples of the Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw and neighboring tribes, Minu-Sepehr notes. At the nexus of these two forces lies a fundamental, yet often obscured, concept: Control of land and water is control of people.

“My research recognizes the profound intersections of colonial settlement to environmental degradation and disruption, as well as intentional indigenous decimation — both of which have lasting effects to this day,” said the cultural anthropology major who is on a pre-med track.

A History Hidden Behind the Map

Minu-Sepehr’s research uses the creative practice of mapping as a form of inquiry. More specifically, she employs an “overdrawing” method, which is a mapping technique developed by one of her mentors on the project, Liska Chan, associate professor and head of the Landscape Architecture Department. By integrating many kinds of data and knowledge, the result is a multifaceted and layered map that views space through a cultural geography lens. It allows viewers to discern the important and complex political and cultural features of a place — details that go far beyond what a conventional map offers.

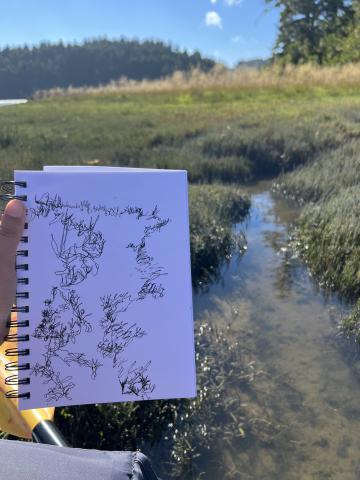

Ava collected, organized, and analyzed data that span multiple academic disciplines. She relied on the Southwest Oregon Research Project database to examine some of the earliest maps of the region; completed extensive background reading about the historic, cultural, indigenous, and environmental histories; used Aeronautical Reconnaissance Coverage Geographic Information Systems (ArcGIS) software to map and interpret Light Detection and Ranging (Lidar) data in the area; and finally, completed multiple site visits to study, situate, and photograph the estuary and important cultural and environmental sites.

Given the breadth of her research, one of Ava’s keys to success was creating a strong network of support, including her project mentors Chan and Jason Younker, assistant vice president and advisor to the president on sovereignty and government to government relations. Her UO peers provided technical assistance and moral support.

“I have been extremely grateful to work alongside people doing very diverse work, from landscape architecture to indigenous studies to estuary rehabilitation,” Minu-Sepehr said.

Overdrawing the Landscape

Within cultural and creative geographies, overdrawing is quite new. Minu-Sepehr's research serves as proof of concept that this approach has the potential to create a fuller, embodied, deeper understanding of landscapes. Her research also contributes to our understanding of the environmental impact of human interventions in water landscape as well as the creation of Oregon through a colonial and/or indigenous lens.

Minu-Sepehr's research forms the basis of her Clark Honors College thesis and Cultural Anthropology honors thesis. Her plan is to give the completed artwork and written components to the libraries of the Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw, as well as the Coquille Indian Tribe.

“My hope is to make my work about these tribes and indigenous Oregonians as accessible as possible,” she said.

Not only has her research made an original contribution to major areas of study, but the experience has also transformed Minu-Sepehr's perspective.

“I have grown in so many ways throughout the course of this research,” said Ava. “It has emphasized the importance of indigenous studies and the profound need to support indigenous work and existence across the U.S. and particularly in Oregon.”