Editor's note: This story is part of The Marathons Series, a collection of articles written by faculty and students. It's a space to talk about work in progress and the process of research—think of it as the journey rather than the destination. We hope these stories help you learn something new and get in touch with your geeky side.

Language is an integral part of how humans interact with each other and the world around us. Of the estimated 7,000 languages spoken around the world, nearly half are at risk of dying out. Numerous language revitalization programs have been started within many of these speech communities, and an important part of that process is the documentation of the language, which allows for language teaching resources to be created.

One of the many linguists studying and documenting endangered languages is Spike Gildea, professor of linguistics at the University of Oregon.

For the last 30 years, Gildea has partnered with Native communities in Brazil to document and analyze the Werikyana language, which today is spoken as a first language by only a handful of people. Gildea began working with this language in 1994, the same year that he completed his doctorate. His philosophy is that the research he does should directly benefit the people who he is working with. As such, it was important to him that the community’s ambitions for protecting the future of their language be centered in this collaboration.

“I belong to a group of people that believes that the best way to do this kind of research is in fact not for you to go and create something and give it to the people, but it’s to work with the people, to help them develop the skills to do it for themselves, and get permission to use what they produce,” Gildea said. “Let me do all the stuff figuring out the phonological problems, the morphological problems, the syntax, and maybe some of that will turn out to be useful to them too, but in the meantime, they’re producing what they need, what they want.”

For his latest project, Gildea is revisiting data that he collected in 1994: An eight-hour recording of a traditional creation story recounted by the last Werikyana-speaking shaman, Txuruwata Cecílio Kaxuyana, just a few months before he passed away. Now that internet access has reached the Kahyana villages, Gildea meets weekly via video call with Werikyana-speaking collaborators (including one of Txuruwata Kaxuyana’s granddaughters) to work on transcribing and translating a portion of this story.

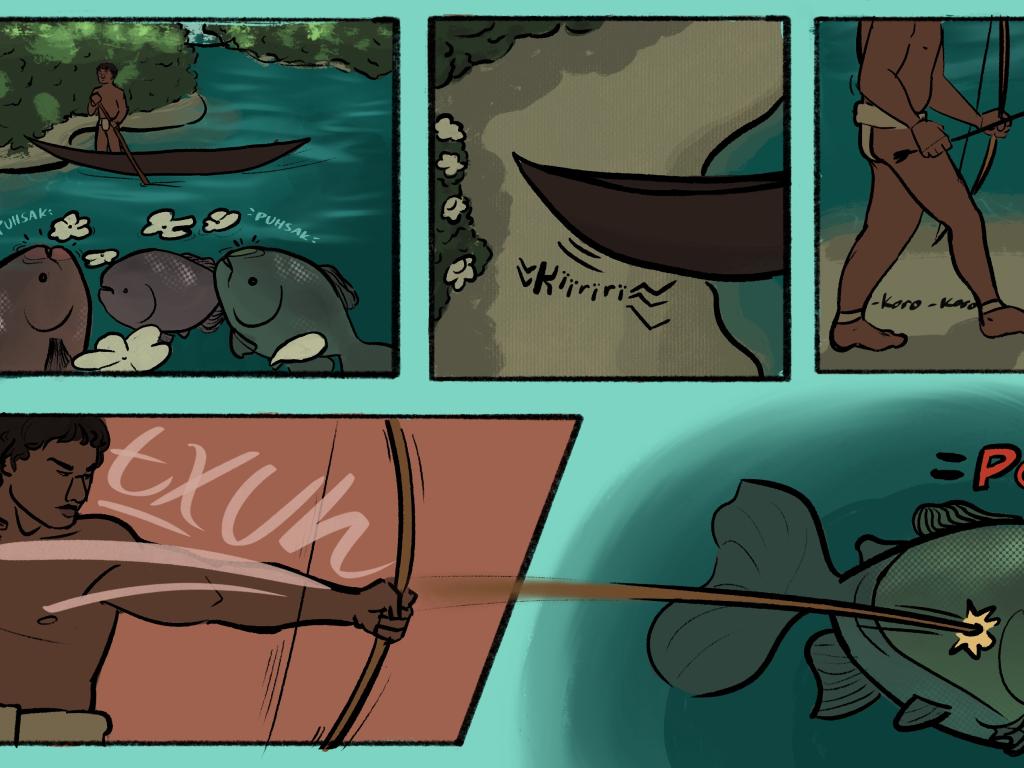

A key feature of this story that caught Gildea’s interest was the amount of ideophones that are used in it. Ideophones are words that serve as sound effects, providing “color commentary” to the core words which describe who is doing what to whom. Some ideophones would also be considered onomatopoeia, meaning that they resemble an actual sound (like the words “pop” or “crack” in English) while others might evoke other sensory images unrelated to sound (like “ta-da” to refer to something being revealed).

Werikyana has many different ideophones, some of which imply common actions and types of movement, some that mark a time of day or the passage of time, some that reflect an experience of emotion, and so on. Interestingly, Gildea notes that there are many instances in this story in which nouns, verbs, and the traditional grammar are not used, and the events are conveyed almost entirely through sound effects.

“There’s no verb, ‘it hit.’ There’s just a sound. So, it’s like saying ‘Thunk! A fish,’” Gildea explained.

At first, Gildea was puzzled at how these words could carry so much information that the audience could follow the story. He has come to understand that in this creation story that has been passed down for generations, the ideophonic words are likely serving a different purpose altogether.

“With these sound words… they rely on people’s knowledge of the story. So, the sound words evoke an image that they already have. So, ‘ɗe!’ sounds a lot more impressive than ‘And then he hit her on the forehead.’”

Werikyana storytelling sessions can go on for eight hours at a time, so part of Txuruwata Kaxuyana’s job as a master storyteller was to captivate the audience. His use of sound words as well as dynamic variation in pitch and rhythm resulted in an enthralling performance, even for audiences who have heard the tale many times before.

Ideophone usage in the Werikyana language provides a glimpse into a rich storytelling tradition. Through the Werikyana-speaking communities’ efforts with Gildea to transcribe their creation story, it may be possible to keep the language and storytelling practice alive through the younger generations.