The human relationship with the natural environment is constantly evolving. Researchers at the University of Oregon take numerous approaches to improve these relationships, build better connections to the world around us, and promote a world with multi-species thriving.

“I fundamentally believe that human well-being is inseparable from well-being of a greater ecological whole," said Erin Moore, professor of architecture and environmental studies and the associate director of environmental studies, summing up a perspective shared by researchers in science and risk communication, geography, art history, environmental studies, and architecture—all of whom bring unique approaches to address environmental concerns and work toward solutions.

Environmental communication from diverse voices

How we talk about the natural environment is influential in shaping our relationship with the world around us. In the University of Oregon’s science communication program, housed in the School of Journalism and Communication (SOJC), several researchers take an interdisciplinary approach to connect science and society.

“(Climate change) is one of the biggest problems facing humanity, and I think addressing it takes an all-hands-on-deck approach,” said John Sutter, assistant professor of science communication. “I don’t think there’s one story that’s going to click and make everyone get it.”

Sutter has an extensive background in filmmaking and climate journalism; his work has won several awards and two Emmy nominations. He is currently working on two documentaries, both focusing on the climate crisis.

Sutter is directing a film currently titled BASELINE that will follow young people growing up in Utah, Alaska, and the Caribbean island Dominica, all places with different “climate signals,” or ways they are impacted by changing climates. The film will follow children from 2020 to 2050, showing how their lives and surroundings change during that time. The inspiration came from a film titled Seven Up!, which followed seven-year-old children in the UK until they were in their 60s. Sutter feels that these long-term projects elicit nostalgia and more emotional responses, which he is trying to harness in his work.

“I feel like we need to keep coming up with new ways of seeing the climate crisis and seeing the change that's happening around us,” he said.

He is also a producer on PLANET A, which follows glaciologist Erin Pettit and a small team of scientists, consisting of six women and one man, a rarity in polar science. Pettiti is a professor in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences at Oregon State University, and the film follows her team on their final journey to Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica. Sutter was interested in telling the human stories not found in scientific papers about the glacier. He wants to exemplify the perseverance of climate change researchers and the multidisciplinary collaboration that tackling climate issues requires.

“This is a big topic for us to all face, and that can be paralyzing, and it's about pushing through that,” Sutter said.

Science communication doesn’t only come from journalists or scientists. Ben Bunquin, a graduate teaching fellow in the SOJC, says that social media has become “one of the top, if not the top, sources of information when it comes to scientific issues.” Bunquin is researching science communication in digital media and is particularly interested in its uptake via TikTok.

In an age of shorter attention spans, science communicators have adapted to new ways of communicating, and more people have gained a voice to talk about science on the internet. A central part of Bunquin’s research is meme-based communications and the use of visual, humorous, and entertaining content to engage audiences.

“If you're a content creator talking about climate change or the environment, one strategy is using solutions communication or positive communication, and injecting urgency into that communication, and at the same time, using meme-based elements, like challenges, trends, background music that can enable your content to spread faster in digital media,” he said.

Bunquin reflects on social media’s role in building feelings of community around climate activism and in making scientific information more accessible to a wider audience.

“It's not just a matter of communicating the solutions that comes to the environment, but also raising urgency,” he said. “On platforms like TikTok, content creators are able to do that because it's a platform that's multi-modal. It includes different media formats all in one package.”

Alex Segrè Cohen, assistant professor of science and risk communication, has frequently collaborated with Bunquin on research related to audience responses to science communication. With her research, Segrè Cohen is interested in “how humans interact with the world around them and how different institutions and power dynamics shape that relationship.”

Her research often falls under the realm of “risk communication,” which she defines as “how people understand different risks and hazards in their lives” and, additionally, how people and institutions communicate about these risks. Many risks in human lives overlap with environmental hazards.

Last year, Segrè Cohen co-authored a study looking into risk perceptions of wildfire smoke based on government communications on Twitter. Based on their findings, the researchers found that as exposure to wildfire-related risks continues to rise, communication about these risks on “popular media platforms” should also increase. Importantly, Segrè Cohen also emphasizes the need for communication to be in line with best practices in environmental and strategic communications. She also says that it’s essential to target communication toward a specific audience and “communicating with people in a way that is culturally appropriate that’s in line with their values, uses the languages they understand, and is meaningful to them.”

Creating “meaningful” communication helps build connections between people and the world around them. Before coming to the UO in 2022, Segrè Cohen worked at a climate justice nonprofit called Our Climate Voices, which centered around “telling stories of people’s experiences on the front line of climate change and how issues of climate change are deeply woven with justice issues.”

She expressed that we are all experiencing the changing climate and are deeply connected to the environment. Environmental storytelling is a tool that can build connection and empathy and improve our understanding of the world around us.

“We’ve all felt anger and hope and fear—that’s part of the human experience—and we’ve all existed in the environment,” said Segrè Cohen. “So, to be able to paint and weave this story about our own experiences and how that connects to this larger web of stories, I think, can be a powerful tool to motivate action.”

Segrè Cohen further explained that when emotional appeals and narratives are paired with scientific pieces like maps, graphs, and numbers, science communication is “stronger and more palatable.”

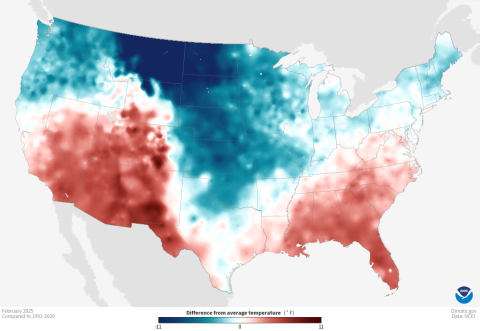

Carolyn Fish, a cartographer and assistant professor of geography, is interested in how maps are used in popular media to communicate topics like climate change. Specifically, her research is interested in how maps meant to talk about environmental impacts are designed, used, and disseminated.

“Maps are a really fast way to consume information,” said Fish. “Being able to get that information quickly without having to read pages of text is a great skill.”

She does, however, emphasize the importance of media and map literacy, saying that people should always question the credibility and origin of things they see on the internet. Other researchers, like Bunquin on the TikTok videos and memes he is studying, agree.

Part of Fish’s research is looking into emotional responses to maps, and she hopes to eventually employ the emotional appeals Segrè Cohen says help make science communication stronger.

“I think it would be really interesting to work with artists in the future trying to make these evocative maps of places that are impacted by changing climate and do some sort of gallery show,” said Fish.

The interdisciplinary approaches to science communication research throughout the UO’s exemplify the need for diverse perspectives and storytelling in communicating about the natural environment.

“Climate change, or any environmental problem, is not field specific,” said Segrè Cohen. “You can’t solve climate change through just journalists or just psychologists or even just politicians. It is an interdisciplinary problem, which means that interdisciplinary work has to be done to solve the problem.”

Visually expressing the environment

We are often bombarded with repetitive information about environmental problems and changing climates, to the point we can end up filled with negative emotions like dread or guilt that lead to inaction. Art, or other creative forms of visualization, can be a means for people to reconnect with environmental concerns and with each other.

“I think art exceeds straightforward communication,” said Emily Eliza Scott, assistant professor of art history and environmental studies and incoming co-director of the UO’s renowned Center for Environmental Futures. “Art has the capacity to newly sensitize us to conditions and often to conditions that are difficult to grasp.”

Further, it “has the ability to make the strange familiar and the familiar strange,” and to help “excavate or amplify submerged perspectives.” In the art that Scott analyzes in her research, these “submerged perspectives” are often tied to individuals and communities who are inequitably impacted by various environmental injustices.

Scott is currently writing a book on art that tracks environmental violence. In each chapter, she features an artist or organization working to make a difference in their community. One chapter, for example, is about the Houston Ship Channel, where a collaborative project by The Natural History Museum and t.e.j.a.s., a Latinx environmental justice group, has brought public awareness to the highly polluted petrochemical corridor and the communities most impacted by environmental degradation there.

“Together, an art collective and environmental justice activists created an exhibition: a set of tours, maps, and billboards that drew attention to toxicity and environmental racism in Houston as well as the petro-capitalism which brings it about,” said Scott.

Joe Sussi, a doctoral candidate in art history working under Scott, focuses on the environmental toxicity that impacts people throughout the world. He is mainly interested in examining how our cultural separation between nature and culture influences our understanding of environmental pollution.

To understand what influences our understanding of environmental pollution, Sussi first looked into what we perceive environmental pollution to be, turning to art for answers.

One chapter of his dissertation follows Karin Bolender, an Oregon-based artist who was once a fellow for the Center for Environmental Futures at the UO, who created handmade soaps to demonstrate how pollutants in our environment cannot be so easily washed away.

He says, “It’s not something that’s literally remediating pollution in our bodies, but it’s a way to think about the different accumulations of environmental pollution within us, and how different spaces put you into contact with such a variable degree of exposures.”

Similarly to Scott, Sussi’s work focuses on the uneven distribution of environmental hazards, both between different groups of humans and between species. His research additionally looks into the ways exposure to environmental hazards is predetermined by systems of racial and gender-based discrimination and cannot be controlled by the people it is impacting.

Building a more sustainable future

The intersection between human and environmental well-being is especially exemplified in the architecture department. As architectural structures have historically been built from almost exclusively finite materials sourced from the natural environment, researchers are looking for ways to build more sustainably and efficiently.

Erin Moore, professor of architecture and environmental studies and the associate director of environmental studies, is interested in incorporating cultural constructions and ideas of nature into the designed environment, bringing our environmental beliefs into the buildings we construct. Moore went into the field of architecture to look into questions related to the connections between the built and natural environment.

"Building environments that are more environmentally just and more ecologically sound requires more than just tools from science and technology," said Moore. "Real change requires advancing cultural thought—change requires paradigm shifts. I have found that the space between art practice and architecture practice that some people refer to as 'critical spatial practice' to be useful for exploring these complicated ideas in environmental justice and ecological design."

The Institute for Health in the Built Environment, embraces the idea of multi-species health and sustainability through a transdisciplinary (across boundaries of scholarship and levels of stakeholders) lens, focusing on individual and collective health. Mark Fretz, assistant professor of architecture and co-director of the IHBE, is involved with a project that is trying to directly impact human and environmental health by creating hospitals out of mass timber.

He says that healthcare is an energy-intensive industry, and using more sustainable materials to build a hospital could greatly reduce the building’s embodied carbon footprint. The Environmental Protection Agency defines embodied carbon as “the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the production (the extraction, transport and manufacturing) stages of a product’s life.”

Along with reduced carbon emissions, Fretz says that mass timber construction stands to benefit visitors’ well-being and experiences in a hospital setting—a space that often engenders anxiety or fear in many people.

Fretz cites research on biophilia, the idea that humans have a desire to connect with the natural world around them, saying, “You can improve patient outcomes in spaces where you’re more connected to nature. One way to connect to nature is through direct views through a window of nature, but another way is to connect with materials that are exhibiting properties found in nature, whether that be fractal patterns found on the wood itself, or the actual color tones and patterns of wood, the smells of wood.”

One main obstacle Fretz and the project have yet to overcome is the acoustic separation between spaces—wood materials carry sound rather than dampen it. The UO is building the Oregon Acoustic Research Laboratory, funded in part by a Build Back Better grant from the US Economic Development Administration, to help further research that will address these concerns.

Charlotte Kamman, a fifth-year architecture and Clark Honors College student, is a student researcher in the IHBE and is working to mitigate acoustic problems with bio-based solutions that have lower embodied carbon.

With Fretz as the principal investigator, Kamman's research investigates acoustic isolation materials, which “decouple sound between neighboring spaces,” made out of mycelium-based composite (MBC) materials. This exploratory research is funded by the US Department of Agriculture's Agricultural Research Service. MBC materials are created by growing fungi on an organic cellulosic substrate, like wood fiber or agricultural byproducts. As the fungi decomposes on the substrate, it binds substrate fibers together to create a foam-like spongy acoustic isolation material.

During the material production process, Kamman was surprised to find the formation of edible oyster and medicinal reishi mushrooms.

“This material production process could allow for the creation of building materials with simultaneous food co-production,” said Kamman. Her project represents an effort to reduce carbon emissions and overall waste and promote a healthier and more sustainable built environment.

The materials created through Kamman’s research are intended for non-healthcare applications because fungi may introduce infection control concerns in hospitals. Fretz shared that the IHBE is currently investigating the indoor microbiome related to mass timber construction to overcome these infection control concerns, while also addressing other issues like acoustic isolation.

Tackling environmental concerns, while also promoting human flourishing, requires collaboration from all disciplines and the creative, innovative, and boundary-pushing solutions coming out of current university research.

“We’re taking these interdisciplinary approaches because all the disciplines have something to offer to help mitigate climate change, so why not do what we can,” said Segrè Cohen.