This past summer, 19 undergraduate students across disciplines participated in the Office of the Vice President for Research and Innovation summer fellowship programs, the VPRI Fellowship and the O’Day Fellowship. These programs give students a more in-depth experience of working in a lab than they might otherwise have. Case in point: One fellow discovered what may be a new species.

“By being able to commit more time to the lab, the students are able to see all the steps of the scientific process, and they are able to take on their own piece of a project and work more independently,” said Ashley Walker, associate professor of human physiology and the laboratory director of the Aging and Vascular Physiology Lab, which summer fellows Lazar Isakharov and Tallula Wynia are a part of.

Faculty and students alike agree that the opportunity to conduct research as an undergraduate student is greatly beneficial for the students and shows them what a future in research could look like.

A kind of photosynthesis: One student’s growth during summer fellowship

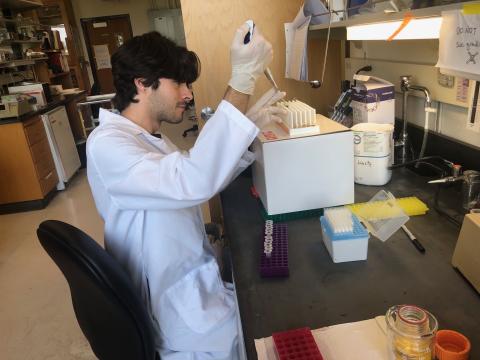

Senior and biology major Paul Graf was part of the VPRI Fellowship program and the Barkan Lab, run by biologist Alice Barkan. Barkan explains that chloroplasts, the organelles within a plant cell where photosynthesis takes place, have their own set of genes separate from the genes in a cell’s nucleus. Graf’s research focused on the gene expression in the chloroplast.

“So, what I’m doing now, is looking at leaf development and how different aged leaves on a single plant express proteins differently and at different levels,” he explained this past summer.

Barkan explained that Graf’s research has found that when young leaves get older, most of the genes shut off in the chloroplast with only one exception. She says that one gene is special because it encodes a protein that is rapidly degraded during photosynthesis and has to be constantly reproduced.

“This has practical implications,” said Barkan. “There are people trying to use the chloroplast genome, this little set of genes in the chloroplast, as a place to express other genes for biotechnological purposes or to change the properties of plants so they’re more resilient in the face of changing climate. There are a lot of different foreign genes that one might put into the chloroplast to help the plant or produce something valuable like a pharmaceutical or vaccine.”

While Graf is no longer part of the Barkan lab, he hopes to continue working in plant biology after graduating from the University of Oregon.

“I’m thinking I’m going to go into a career in plant biotech, specifically in crop plant manipulations, like making them more disease resistant or drought resistant, more nutritious, or making them make some sort of pharmaceutical products for us,” Graf said.

Barkan says that working full-time in the lab greatly benefits undergraduate students. She explained that her role in the lab is as an educator, spending time training and mentoring students, with help from other lab members.

“The benefit for them is enormous,” she said. “I just see this over and over again, compared to squeezing in an hour there, an hour here during the school year, and they don’t really get what’s going on and they’re not really immersed in the research. They advance really slowly during the school year, but you put them in the lab full time for 10 weeks over the summer and everything starts clicking together.”

Oak savanna research leads to discovery of potential new species

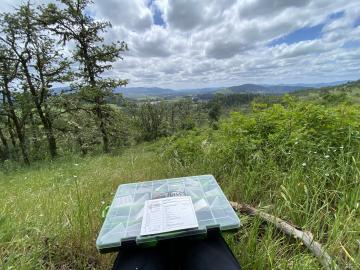

It’s not every student who can say they may have discovered a new species during their summer research project. Senior Kyla Schmitt is a double major in environmental science and humanities, as well as a student in the Clark Honors College at the University of Oregon with minors in English, biology, and economics. This summer Schmitt, along with her graduate student partner Ethan Torres participated in the O’Day Fellowship for Biological Sciences. Schmitt says that her research takes place “at the intersection between ecology and biology.”

Her project and Torres’ work overlap between labs in the Institute of Ecology and Evolution, including associate professor Jeff Diez’s lab, retired professor Bitty Roy’s lab, and associate professor Lauren Hallet’s lab.

As part of her research, Schmitt did vegetation surveys to see how the understory plant life interacts with the fungi in the area. In mid-October, through these surveys, she found a potentially new fungi species in the genus Ceriporia, which are crust fungi.

Torres has been helpful in guiding Schmitt through the process of doing vegetation surveys and inputting the data into usable formats for analysis.

“We went out together and he showed me the ropes with how to identify plants and how to use these plots that are meter-squared PVC pipe frames, that you place down and you estimate the cover of plants within that square and what species are present,” she said. “I had never done that before this summer, so he was a massive help in showing me how to do that and helping me with some of my data collection.”

Schmitt’s data collection took place in the oak savanna regions in Eugene—displaced and endangered habitats of primarily prairie areas with some oak cover that used to cover the Willamette Valley before settlers arrived. She explained that oak trees have symbiotic relationships with fungi. The research sites include areas around Mount Pisgah and other naturally occurring sites throughout Eugene.

“The goal of my project is to map the fungi in these oak savannas, first off, and then second off, to compare groups of oak savannas that have recently been burned and those that have not been burned,” Schmitt explained. “So, looking at how that community changes when there is a presence of fire versus not, as well as the recency of when that wildfire burned.”

While her work is mostly science based, she says that there are likely policy and political ramifications for her work. She is particularly interested in how her focus on how fire changes a landscape can work with Indigenous traditional fire management practices.

“With the project looking specifically at how fire impacts fungal and plant community responses, we’re really hoping to advise fire management as a policy and supplement that traditional knowledge,” Schmitt said. “So, when governments or nonprofits are trying to manage their own land, the outcomes of this research could help them better understand the effects that this sort of habitat maintenance burnings might have on fungi and plants.”

Along with Torres, Schmitt found mentorship in Heather Dawson, a doctoral student, in the Institute of Ecology and Evolution. While Schmitt’s project focuses on the above-ground fungi, Dawson’s research centers on underground fungi such as truffles. Schmitt says that their projects are different parts that fit into the same network of research questions and methodologies. She gives credit to Dawson for coming up with a lot of the ideas for their projects and developing methodologies.

Schmitt hopes that the two can write a paper on their collective research someday because of how similar the projects are. After graduating from the University of Oregon, Schmitt wants to find a way to combine her interest in science and writing.

“I’m hoping to be a seasonal worker for a while and then at some point, I would love to come back to academia and work for a journal or some sort of culmination of science and writing,” she said.

Participating in research with global impact

Senior and biochemistry major Zach Marshall is part of associate professor of neuroscience and human physiology Adrianne Huxtable’s lab. Huxtable’s lab studies how early life stressors impact breathing, particularly looking at how the brain and spinal cord control the muscles that allow people to breathe. Marshall’s project examines how neonatal viral inflammation may have effects on adult respiratory control. He’s specifically looking into how a previous stressor, such as viral inflammation can undermine the propensity for plasticity. Marshall defines adult respiratory plasticity as “a change in your brain’s control of breathing based on past experience.”

“So, basically, if you get a viral infection as a neonate, like a very young child, that causes inflammation and we're studying how that inflammation causes damage to your brain's ability to control breathing as an adult,” he explained.

Marshall says that there’s urgency in projects like his because of the increase in viruses like COVID-19 and Zika, especially since the number of children getting these viruses is also increasing.

“Once you have that inflammation, once your plasticity is abolished, it can really disrupt how your body reacts to illnesses and disease as an adult,” he said. Part of his project is looking into anti-inflammatory pharmaceutical interventions.

Moving forward, Marshall hopes to publish his findings by helping write a scientific manuscript. The Huxtable lab is small, and while Marshall found comfort in his previous lab experience because the larger labs are beneficial learning sites for undergraduates with many other researchers at many different levels, he says it’s great to have this increased responsibility in a smaller lab. Huxtable says she will intentionally always have a small lab because she appreciates individual interactions and the opportunity to be more involved in the projects her students are working on.

Last year, Marshall was part of the VPRI Fellowship in the summer and received an OVPRI Mini-Grant in the fall. Huxtable says that having undergraduates full-time over the summer is mutually beneficial for the faculty and the student.

“Research is hard, and I think it’s hard to make progress and be trained in the complicated techniques and get the full benefit and understanding of what research looks like without some sort of full-time experience,” she said. She explained that just as it’s difficult for a student to balance classes and lab work during the school year, it’s also hard for faculty to balance teaching and research, so it’s beneficial to “have more protected time to really dig into the questions they’re asking.”

After graduation, Marshall plans to go to medical school and eventually work in pediatrics. His interest in child development is part of what drew him to this lab in the first place. This past summer, Zach was able to observe and learn how to do some more medical leaning parts of Huxtable’s research, such as surgeries. Huxtable hopes that the researchers in her lab learn and grow from their research.

“My goal is to train good scientists,” she said. “Whether they stay in science or not is irrelevant. I think the experience of learning and understanding how we do good science is really important.”

I Know What You Did Last Summer

Our summer fellows have been conducting innovative research in their labs throughout the summer and into this academic year. We invite you to read the stories below to get to know other fellows and their work.

Elena Kuypers, VPRI Fellow: Career paths and RNA pathways

Undergraduate research experiences help students explore interests and consider career options.

Lazar Isakharov, VPRI Fellow: Undergraduate researcher investigates zinc and Alzheimer’s disease

Isakharov is researching the potential of dietary zinc to prevent the increasingly common disease.

Nico Burns, VPRI Fellow: UO fellow is as busy as a bee

Burns is investigating strategies to reduce pollinator population declines and find new habitats for them.

Olivia Estes, VPRI Fellow: Exploring ketamine's potential for reducing Alzheimer’s symptoms

Estes is one of multiple people on campus conducting science that may one day help treat Alzheimer's disease.

Riley Acker, O’Day Fellow: Brainwaves influence ability to remember and create memories

Undergraduate researcher studies the creation and retrieval of memories

Tapley Sorenson, VPRI Fellow: Biological sex differences and sleep

A summer spent investigating how biological sex differences influence sleep cycles.

Tallula Wynia, VPRI Fellow: Research explores the effects of artery stiffness

Undergraduate research aims to understand the mechanisms behind arterial stiffness.