Editor's note: This story is part of The Marathons Series, a collection of articles written by faculty and students. It's a space to talk about work in progress and the process of research—think of it as the journey rather than the destination. We hope these stories help you learn something new and get in touch with your geeky side.

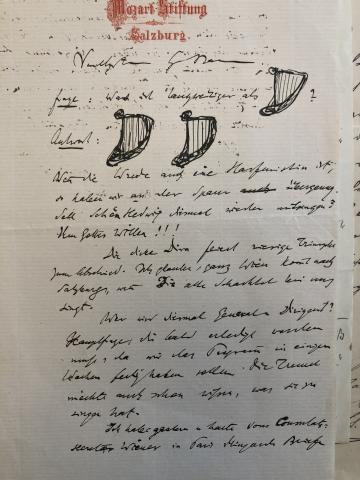

Archives are disorienting. Imagine: it’s summer in some European city. In the streets, a lazy river of tourists overflows its banks. You elbow your way through an alley to a historic façade with gold lettering. Up the narrow stairs, past the exhibits, you arrive at an archive in the rafters. The archivist shows you to what she calls the “holy treasure room,” hinting at the relic repositories of churches. On a quest for relics, you pull open one file drawer after another, rifle through an 1880s card catalog, and wander through floor-to-ceiling shelves of boxed protocols.

The initial thrill cedes to weeks of tedium and the frustrations of faded ink, abysmal handwriting, the runes of secretarial shorthand, the dawning realization that you will absolutely never see the bottom of the pile. You must be an antiquarian to do this work. That’s an embarrassing realization after reading Nietzsche: In 1874, he wrote that the antiquarian’s soul “prepares for itself a secret nest” made up of “the small, limited, crumbling, and archaic.” We all know those secret nests. Antiquarians collect ashtrays, decorate the house with daguerretoypes, and love the smell of decayed paper. That smell is easier to love in theory. In the archive, every box coughs up a cloud of vinegar, rotting leather, and rainsoaked wool. (From a book called Dust by Carolyn Steedman, I learned that a historian around 1830 fretted about breathing in the particles of the dead, which sickened his spirits and anticipated what Jacques Derrida later called “archive fever.” She suspects it was just anthrax.)

Historians who work in archives are torn between the romance of discovery and the banality of sifting. Every research method has its own special banality, of course: data collection, coding, mounting zebra fish parts to a plate. For many historians, archives are just a means to an end, as the real thrill lies in the gradual deepening of a question. I work in archives to study the very reason archives exist: the 19th century’s obsession with preservation, collecting, and relics, which is the subject of my new book, The Composer Embalmed: Relic Culture from Piety to Kitsch.

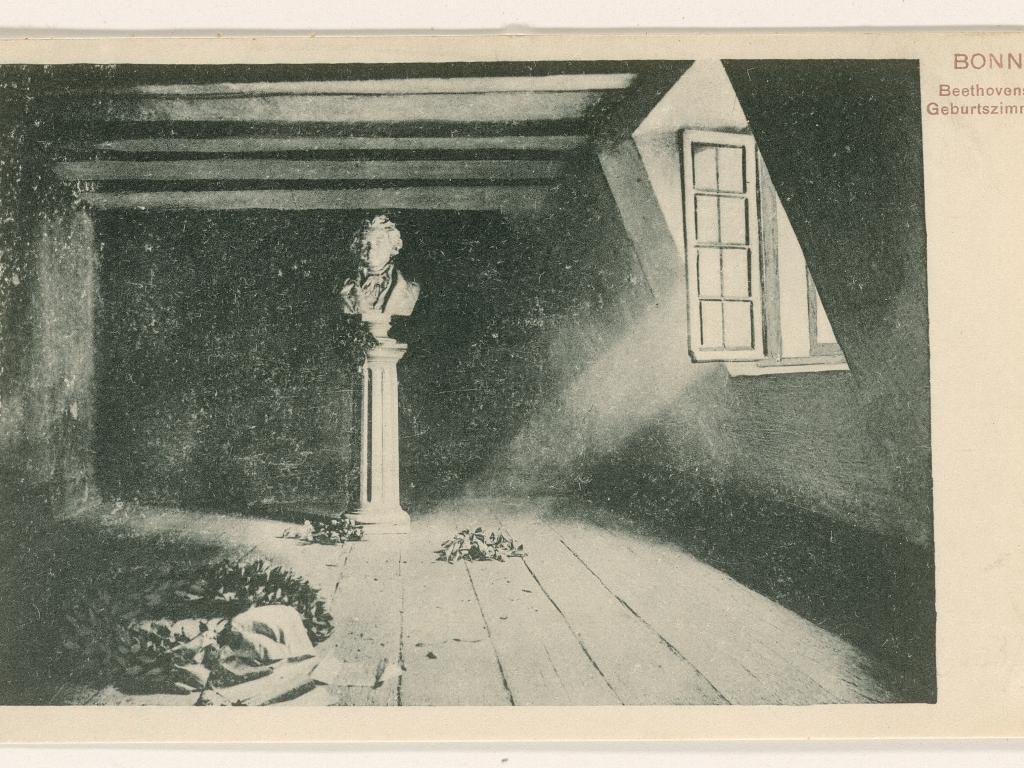

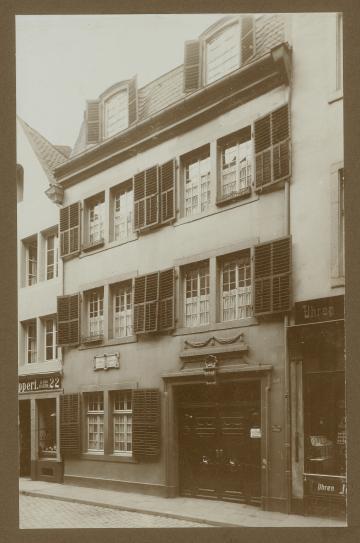

Relics and embalming can be metaphorical as well as literal. Take for instance the houses where composers lived or died. Many of these were ordinary dwellings until their inhabitants were evicted to reenact a sense of the composer at home, a shrine frozen in time.

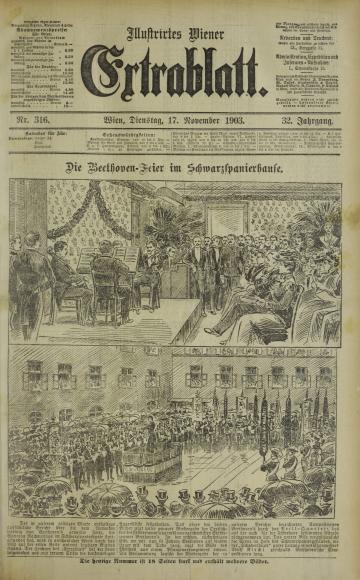

For some, these houses were ersatz bodies. Before Beethoven’s death-house was demolished in 1903, fans gathered at a funereal ceremony to see it off. Some said Beethoven’s spirit was desecrated; others said it was trapped, and the bulldozer would free it from the walls. A few collected stones from the rubble. One man commissioned a carving of Beethoven’s face and hung it on his wall. This is what I call “relic culture.”

I’m no psychoanalyst, so I can’t diagnose archive fever. But by the end of writing this book, I did feel a bit suffocated by the volume of stuff we preserve. One problem lies, I think, in the awkwardness of archiving ourselves. In the nineteenth century, the display of composers’ death masks, manuscripts, and quills coincided with early anthropology museums stuffed with trophies of empire. In a memorable remark, the essayist Georges Perec demanded that we “question our teaspoons”—that is, we should create an anthropology not of the exotic, but the “endotic,” the Western study of the self. To concertgoers, Beethoven and Liszt are almost too familiar. But jewelry made from their hair can both fascinate and repulse, as it reflects an obsolete approach to the dead body as memento, whereas we now hold the dead at arm’s length.

These are rare objects, but they are no longer cherished family relics. The archive is their morgue. They are torn from their plush rooms and from the collectors who loved them, wheeled out in a box, set on the table under a bright light. This is actually for the best, so that musicologists immersed in Western culture can examine European heritage critically. In 2015, to my astonishment, an archivist brought me a lock of Beethoven’s hair set in a brooch. (“I’m studying composer-relics,” I had said. Who knew they would bring me organic matter?) I recall that a single stubbly hair poked out from the seam. Without thinking, I touched it. At first I felt a secular sort of emptiness, because the archive did its work, then I was hit with a wave of shame at my blasphemy. As it turns out, the lock might not have been Beethoven’s. In 2023, genomic testing showed several extant locks to be inauthentic. When relics lose their aura as forgeries, or as mute artifacts in the archive, they become all the more interesting. They expose the lasting desire to possess something real and intimate, and they force us to ask: what do I want this relic to be? What do I want from the past?

We often go into archives thinking we’re studying someone else. While researching relics, I found archival work to be more endotic than I expected. At first, the archive seemed like a lesson in patience, but over time, it became a lesson in the self.

Read an interview with Abigail Fine about her book on the School of Music and Dance website.