Studying something as vast as the universe—replete with black holes, exploding stars, and innumerable galaxies from spiral to lenticular—is not a solo undertaking. Physics research is by necessity a group project, with dozens to hundreds of individual names listed on the field’s research papers.

University of Oregon researchers are among those names, with several scientists serving in leadership roles at some of the most significant international collaborations. These include studying high-energy particle collisions ATLAS experiment at the CERN particle accelerator, looking for dark matter deep underground with the SENSEI experiment, observing black holes from rural Washington state, and service on the Particle Physics Project Prioritization Panel—all major players in humanity’s efforts to further understand the universe. And even the secluded Pine Mountain Observatory, operated by the UO in the Deschutes National Forest (at the western edge of some of the darkest skies in the United States), contributes daily to unraveling secrets of the worlds beyond our own.

ATLAS

“Particle physics in general is trying to understand the universe through its most basic constituents: individual particles and the interactions between them that make up everything in the universe,” said Eric Torrence, a physics professor at the University of Oregon, member of the Institute for Fundamental Science. Torrence is the current ATLAS (A Toroidal LHC ApparatuS) run coordinator at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN). The 17-mile particle accelerator at CERN is the archetype for moving fast and breaking things: It smashes particles together at near-light speed to simulate conditions of the early universe in all its explosive glory. The accelerator runs 24/7 for nine months of the year.

In his role as run coordinator, Torrence is making the decisions about how the particle detector is operated and what data is collected. The ATLAS project is looking for exotic signatures—those of invisible particles that could help explain phenomena like dark matter or expand our understanding of the Higgs boson particle (and whether there are more like it).

“Even though we produce tens of millions of collisions every second, the interesting things we are looking for are very, very rare,” Torrence said. “For discoveries, we are looking to see a handful of events in an entire year.”

Read more about 40 millions collisions a second: Cracking the cosmos

SENSEI

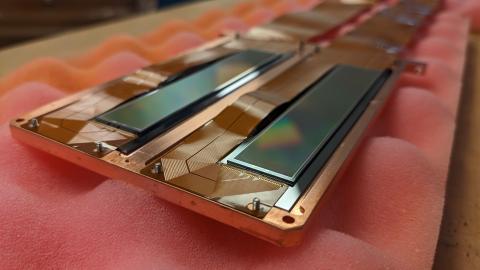

Tien-Tien Yu, associate professor in the Department of Physics in the College of Arts and Sciences, is a core member of the Sub-Electron-Noise Skipper-CCD Experimental Instrument (SENSEI), which is looking for a way to visualize dark matter scattered off electrons.

“There is a zoo of dark matter candidates and direct detection is a powerful way to differentiate between these different candidates,” Yu said. “Traditionally, direct detection looked at dark matter scattering off the nucleus of an atom, which was good for certain types of dark matter candidates. However, if the dark matter has a mass less than a proton, known as sub-GeV dark matter, then nuclear scattering doesn’t work as well. Electrons are much lighter than a nucleus, which helps us get around the challenge that sub-GeV dark matter doesn’t transfer as much energy to a target.”

Yu is fond of the metaphor of the nucleus as a bowling ball and sub-GeV dark matter as a ping pong ball. It’s hard to move the former with the latter. But dark matter is necessary for the formation of the elements that make up our universe, so Yu and her collaborators continue to creatively theorize and then experiment on how they might observe dark matter.

“The Higgs-Boson was predicted to exist in 1964. In 2013 we finally seen the Higgs for the first time and now we can study it in detail. We can do the same for dark matter,” she said.

Read more about dark matter: A researcher takes on one of the unsolved mysteries of the universe

P5

Yu has also served as a member of the P5, or Particle Physics Project Prioritization Panel, an advisory group convened approximately every 10 years by the Department of Energy and National Science Foundation.

Along with 30 other leading individuals from institutions across the globe, Yu helps determine the projects in particle physics that will be funded over the next decade. Via the High Energy Physics Advisory Panel, to which it reports, the P5 informs the funding strategy for both agencies for the next 10 to 20 years. The goal is to identify opportunities for the greatest impact and progress in the field.

“Research in particle physics is an international effort,” Yu said, “and we need to consider how the various efforts, both existing and proposed, within the United States will fit in a global context in the international community of particle physics.”

Read about setting the national physics research agenda: UO particle physicist appointed to national panel

PMO

Perched atop a mountain at an elevation of 6,300 feet, the Pine Mountain Observatory (PMO) in the Deschutes National Forest provides undergraduate students with hands-on research opportunities. Operated by the UO, the observatory features two research-grade telescopes used for asteroid characterization and “ground truthing” the discovery of exoplanets for NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) mission, which discovers planets outside of our solar system.

PMO also hosts the Astro ARC, an annual year-long community-based program where 20 students from all fields of study develop an understanding of the operations of a scientific facility through hands-on experience at PMO. In addition to supporting university research and education, the observatory runs a robust public outreach program where PMO students and staff work with K-12 schools throughout Oregon, hosting roughly 1,500 public visitors each summer. “

This is the ‘little observatory that could,’” said Scott Fisher, PMO’s director and IFS member. “Using a telescope about the size of your kitchen table, we can detect planets orbiting other stars, which allows us to confirm their existence and learn about their properties. PMO has confirmed 15 exoplanets for TESS in the past two years.”

Learn more about PMO or plan a visit this summer: Pine Mountain Observatory

LIGO

Closer to home, IFS members wrapped up a fourth observing run at the Laser Interferometer, Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in Hanford, Washington. This latest run was notable: More than 100 new binary black holes—two black holes orbiting each other on an eventual collision course—were detected.

Of particular interest to Ben Farr, associate professor of physics and IFS director, is the detailed study of black hole populations this trove of signals enables. In 2015, LIGO made the first direct detection of gravitational waves. Members of IFS worked as part of the global collaboration that enabled this discovery, and which earned the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics. During the following decade, LIGO and its partner observatories Virgo and KAGRA have continued observations, recently releasing their newest catalogue containing more than 150 detected mergers. Each signal observed represents one the most precise measurements humans have made—that of space-time stretching and squeezing by one ten-thousandth the width of a proton.

“Black holes have long captured humanity’s interest, but we know surprisingly little about how they form, especially in binary systems like those responsible for producing gravitational wave signals,” Farr said.

He co-led the collaboration’s newest paper studying black hole and neutron star populations with the most recent catalogue. “Our observations provide the most direct means of studying these black holes and have the potential to revolutionize our understanding of how and where the stars that make them live and die.”