Editor's note: This story is part of The Marathons Series, a collection of articles written by faculty and students. It's a space to talk about work in progress and the process of research—think of it as the journey rather than the destination. We hope these stories help you learn something new and get in touch with your geeky side.

The act of visiting a museum peppers popular culture. Recall Tom Hanks dashing through the Louvre in The Da Vinci Code. The Kincaid twins sleeping in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the novel The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler. Ben Stiller’s night watchman discovers that all the displays come to life in Night at the Museum. Debbie Ocean and her team of dazzling thieves attempt to steal a diamond necklace during the Met Gala.

From these examples alone, it’s clear that visiting a museum is about more than a whiling away a couple hours. Museums represent what a culture values. They are participants in the weaving of history and serve as community gathering places. And visitor’s experience at a museum is as important as the works on display. Recent worker strikes at the Louvre demonstrate this last point in particular; delayed renovations have made it difficult for patrons to visit the museum and even more trying for its staff to work there.

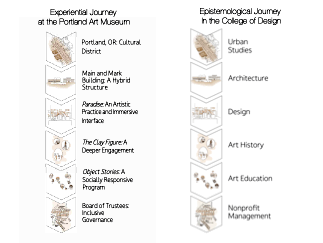

The visitor’s experience at the art museum specifically was the jumping off point for my book: Visiting the Art Museum: A Journey Toward Participation. The book is structured as a journey through disciplines—urban studies, architecture, art history, art education, and nonprofit management. It offers museum visitors a way to reflect not only on what they see but on how knowledge about art museums is constructed. By exploring the museum visit as a process of epistemological transformations that unveils how academic disciplines create knowledge, the book invites readers to engage more deeply—and more critically—with their own experiences.

Writing from Experience

My mind is always on a journey to discover and wander. I love traveling. I love art museums. And I love working in academia—my academic home is in the School of Planning, Public Policy, and Management, where I specialize in American cultural policy, with a focus on the arts, humanities, and historic preservation. Cultural policy enriches everyone’s cultural life—whether through local museums, historic sites, or arts programs—but often people do not realize its impact because culture making works quietly behind the scenes.

When I arrived at the University of Oregon in 2013, I engaged in conversations with my new colleagues throughout the school and wandered the hallways, where I could read the descriptions of their classes. I started seeing the connections among the different academic disciplines in the School of Design, especially as they connected to the art museum and the issues I would address in my classes and my research. Based on conversations with professors in the different departments, I designed a course that I’ve been teaching ever since: “In and Out of the Museum.”

The class evolved over time—initially taught with the Portland Art Museum as a living case study—and it became a central thread in my teaching practice. Then, during my 2020 sabbatical in Italy, the COVID-19 lockdown gave me unexpected space to reflect. I received my bachelor’s degree in philosophy from the Università degli Studi di Milano with Carlo Sini as my advisor and rereading his work, I saw that his ideas had long shaped my approach to research , looking for understanding how knowledge is produces and how academic disciplines intersects.

How Student Experience Informed the Book

Visiting the Art Museum: A Journey Toward Participation unfolds as an edited volume, with chapters by different authors who are enthusiastic scholars in each discipline. The chapters display a variegated world of ideas, values, and writing styles. The common thread is the question: What can museum visitors learn about a specific aspect of their experience from this discipline? In short, this volume started as a class project in conversation with students but took shape as an intellectual journey that connects back to my undergraduate studies.

This past spring, I used my book as a textbook in my Clark Honors College class, “Visiting the Museum.” Each week the students, who hail from a variety of majors, wrote responses to a new chapter—bringing the book to life and connecting it with their own experiences. I’m glad to share a few of their comments here.

“Urban studies talk about how museums connect with cities and the people who live there, and some readings show how they can help bring money into a town and improve areas that were once seen as run-down. But I’ve noticed that big museums are often surrounded by fancy restaurants and tourist attractions. Little to no amenities for those who live nearby, making it a residential dead zone.”

—Dak, comment on the chapter Nuccio, M., & Ponzini, D. (2023). Cities and Urban Studies: Four Perspectives on Art Museums (pp. 27-46).

“Without incorporating art history into our interpretations, we’re simply projecting ourselves onto the artwork—which limits our understanding. Context matters because artworks and exhibitions are never neutral. There are always influences at play, and we have to consider them.”

—Emily, comment on the chapter Walley, A. (2023). Artworks and Art History: Toward a Deeper Engagement with Art Exhibition and/as Art (pp. 87-108).

“Nonprofit management showed me how museums have to balance professional strategies with community values. Not all communities want the same experiences from a museum. I don’t think most visitors realize how much collaboration goes into shaping what they see. If more of that process were shared, maybe the public would feel even more respected and included.”

—Nicole, comment on the chapter Redaelli, E., & Mason, D. P. (2023). Participation and Nonprofit Management: Toward Inclusive Governance (pp. 129-147).

Eleonora Redaelli is a professor in the School of Planning, Public Policy, and Management.