Editor's note: This story is part of The Marathons Series, a collection of articles written by faculty and students. It's a space to talk about work in progress and the process of research—think of it as the journey rather than the destination. We hope these stories help you learn something new and get in touch with your geeky side.

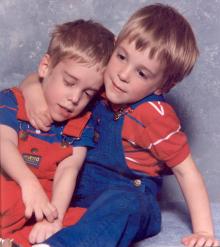

When I was 18, I worked as a camp counselor for people with disabilities. During a pool party, one of my campers escaped in his power chair and drove onto a nearby highway. I had a deep bond with him because he reminded me so much of my own twin brother. Like Danny, he had severe cerebral palsy and intellectual disabilities, could only say a dozen words, and shared the same impish smile. The thought of my camper in danger was deeply upsetting. What’s more, I was supposed to be watching him, and he’d somehow slipped from my care. In the end, he was rescued from the road and returned to camp with a big grin on his face. But the incident haunted me: Did he escape as a prank? As an epic act of protest? Was he trying to hurt himself? Or did he just want to go home?

These questions formed the initial inspiration for my debut novel, Range of Motion, about twin brothers Michael and Sal. Before I started writing, I read every novel and short story I could about characters with cerebral palsy, intellectual disabilities, or communication impairments. With few exceptions, people like my twin brother had been left out of literature. In Sal, I wanted to create a character like Danny, who had significant intellectual and communication disabilities but was also funny and playful, affectionate and exasperating, complex and sometimes a jerk.

I began the book in 2009. I found the writing slow-going. I stopped and started and stopped again. But when Danny died in 2011 at age 28, I found I could travel into a fictional world where someone very much like Danny was still alive, and someone very much like me could still feed him, sing him songs, guide his chair down a church aisle, and make jokes while giving him a shower. Deep in grief, I got lost in my material. I went into my imagination and lived us again.

One day, I wrote a scene in which Michael, as a young child, starts to “hear” Sal’s thoughts. It was a play on twin telepathy, but I had often felt like I knew what my brother was thinking as I interpreted and supplemented his twelve words, his dynamic body language, and his silences. It was compelling for me as a writer to literalize the metaphor in fiction and transgress the boundaries of realism. Was Michael really hearing him? Or was he just imagining him, projecting into the gap? Was he giving his brother a “voice” or was he taking it away? And what would happen if as he gets older, he loses the ability to “hear?”

Now the escape at camp gave an urgency to new questions: Can you ever truly know another mind? How might we trouble the boundaries between normal and abnormal? How should we treat our most vulnerable humans? And what is the difference between speaking for and speaking with?

With this new shape in mind, I finished the book and sold it in the summer of 2024. Fifteen years after I began those early drafts, Range of Motion will be published by Acre Books in October of 2025.

At times, I wondered if I should narrate from Sal’s perspective. In life, I so wanted to know what Danny was thinking and feeling. In the end, I was much more interested in dramatizing and deepening that mystery rather than falsely solving it with narrative. I settled on exploring the twin relationship using close third POV from Michael and then their parents: their neuroscientist father determined to succeed in his research and their stay-at-home mother devout in her care and her Catholic faith. Initially based on my own parents, these characters took on a life of their own as I explored their marriage as another kind of twinship, and imagined how their relationship might become fractured as Sal’s health deteriorated and they struggled against an inadequate social safety net. Through their perspectives, I wanted to create Sal as a truly interdependent character, knowable to the reader through his family as they supplemented his dynamic communication with their own interpretations of his interiority.

Most of all, I wanted the novel to be funny. The tone in my household was one of pervasive humor in the shadow of surgeries and sickness. My goal was to depict this particular comic spirit while being honest about the challenges people like my brother and my family faced. I wanted to tell a stranger, funnier, and more complex story than the usual sentimental and tragic narratives that simplify disabled people and their families. I often think of this Djuna Barnes quote from her novel Nightwood: “There is more in sickness than the name of that sickness.” With Range of Motion, I wanted to show readers that “more.” I wanted to explore the pleasures and anxieties of caregiving and interdependence, the comedy of trying to speak for someone and often failing, and the joy of sometimes getting it right.